Reflections on starting up a disability-inclusive pre-service teacher training project in Liberia

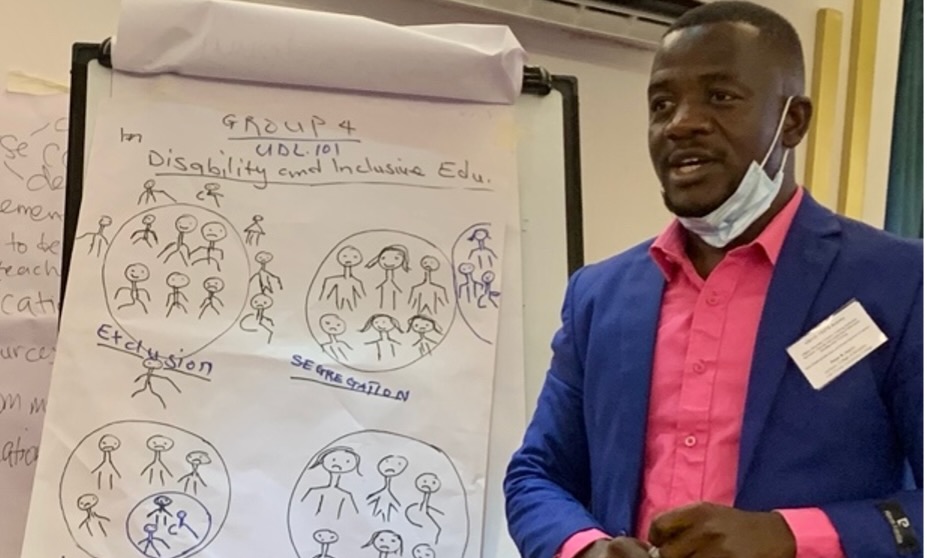

Peter B. Harris, a lecturer at Lofa County Community College teaching UDL for the first time, practices teaching on inclusive education at the August 2022 training workshop. Photo credit IDP.

By Hayley Niad (IDP) and Ricardia Badio-Dennis (RTI International)

Inclusive Development Partners (IDP) is thrilled to be working on the USAID Liberia Transforming the Education System for Teachers and Students (TESTS) Activity. Led by RTI International in partnership with Mississippi State University (MSU), IDP, and Diversified Educators Empowerment Project (DEEP), TESTS is working with 8 higher education institutions in Liberia to train at least 3,500 pre-service teachers studying early childhood education or primary education. A major part of this project is ensuring that future teachers are prepared to be inclusive educators for students with disabilities in general education settings. What does it mean in practice to prepare inclusive educators? How is this lofty goal achieved? This is the work that IDP and TESTS team have been trying to unpack over the first year of project implementation. These are some of the lessons we have learned so far:

- It is essential to develop a shared definition of ‘disability’ and ‘inclusive education’ early on in a project, involving all key stakeholders. In Liberia, disability is commonly known as hearing, vision, or physical disabilities, and nothing more. In a global context, we know that disability can mean many other things, such as intellectual disability, learning disability, speech and language disability, autism, and more. In particular, we know that many people have disabilities that we cannot see by looking at them, a concept that is new to many stakeholders in Liberia. IDP and the TESTS team have worked hard to raise awareness of the varied forms of disability, and what this means for delivering an inclusive education in general education settings. While ramps, braille, and sign language are all incredibly important, we are working to ensure that Liberian educators understand inclusive education means more than these things.

- Providing training to all stakeholders on Universal Design for Learning (UDL) helps to build a strong foundation. What does it mean to provide an inclusive education in a context where there are few resources available to identify who has a disability? The TESTS activity is working off the assumption that there are students with a disability in every classroom in Liberia, whether teachers know who they are or not. A teaching approach grounded in UDL helps to increase the chances that students with diverse learning styles will have their needs met in a context with few available resources. It shows teachers that there are simple strategies they can use in their classroom without expensive assistive technologies or specialized materials. At the same time, it is important to clarify that UDL is the foundation for all, but some learners may still require individualized support (such as access to materials in braille or sign language interpretation). There is a long way to go in this regard!

- Principles of inclusion must be embedded into all aspects of project design. USAID did a great job of embedding inclusion principles into all aspects of their solicitation for TESTS, and attaching a budget to these aims, which has helped the implementation team immensely to ground its approach to inclusion throughout all its work. IDP has conducted trainings and provided informational resources to all TESTS staff on disability-inclusive education, from the technical team to the operations and administrative staff. The TESTS team has also begun sharing these trainings outward to the participating higher education institutions and government leadership. Each person in this project has an essential role to play in promoting inclusive education, and we are doing our best to make sure that this work is collective and underpins every activity, not siloed or segregated.

- “Nothing about us without us.” To ensure that the voices of persons with disabilities are represented in all TESTS work, we have created a Gender Equity and Social Inclusion (GESI) taskforce composed of women and men with and without disabilities, from government, non-governmental organizations, organizations of persons with disabilities, and higher education institutions. The GESI taskforce serves as a guidance and advisory body to ensure the approaches TESTS takes are appropriate to the Liberian context. In turn, taskforce members have also benefitted from training, guidance, and information sharing. As the project enters its first year of providing scholarships to future teachers with and without disabilities, the GESI taskforce will continue to play an important advisory role.

Building inclusive education systems is not an easy task in any country. In the case of Liberia, we benefit from a highly committed and passionate group of colleagues and partners, which helps to propel this vision forward. We are grateful to those at the Ministry of Education, National Commission on Higher Education, and participating higher education institutions, among many others, for their genuine interest and support in the pursuit of an inclusive Liberia.